Media Coverage

Godavari Biorefineries Raises $15 Million from Mandala Capital

LIVEMINT.COM | May 13, 2015

The funds invested by Mandala will be used for a new manufacturing plant for specialty chemicals and strengthening the company’s utility infrastructure.

Godavari Biorefineries was established in 1939, and has sugar, ethanol, power and chemical plants in Karnataka and Maharashtra. Godavari expects a turnover exceeding Rs1,200 crore for the financial year 2016.

Mumbai: Godavari Biorefineries Ltd, a manufacturer of biofuels and specialty chemicals, on Tuesday announced that it has raised $15 million (Rs.90 crore approximately) in equity funding from private equity firm Mandala Capital.

“In recent years, Godavari has been following a strategy focused on creating higher value than its peers globally from every unit of its feedstock, be it sugarcane, molasses, ethyl alcohol, bagasse or, in the future, any other biomass,” the release said.

“Our focus is on developing new production processes to manufacture specialty and high performance chemicals using biomass as raw material within the value chain,” said Samir Somaiya, chairman, Godavari Biorefineries.

Godavari Biorefineries was established in 1939, and has sugar, ethanol, power and chemical plants in Karnataka and Maharashtra. Godavari expects a turnover exceedingRs.1,200 crore for the financial year 2016.

Mandala Capital manages private equity funds that invest in companies focused on the agribusiness sector in the Indian subcontinent.

On 1 April, Jain Irrigation Systems Ltd announced that its non-banking financial company Sustainable Agro-commercial Finance Ltd raised Rs.112 crore ($17.9 million) from Mandala Capital.

Click here to download the pdf file.

Sustainability Yeilds Sweet Success

CEN.ACS.ORG | Jun 01, 2015BASIC ECONOMICS TEACHES that companies exist to maximize their profits. Godavari Biorefineries, an Indian producer of sugar, ethanol, and biobased chemicals, didn’t get that memo. Its managers appear focused as much on philanthropy and sustainability as they are on generating a financial surplus every year.

It’s an unconventional approach that is working for the firm. Sales at the 76-year-old company have risen steadily from $160 million in 2010 to $202 million last year, according to a recent financial report. Investors seem to like what they see. Godavari succeeded in securing a $15 million cash injection last month from a private equity fund.

Godavari is an unusual company. On the one hand, it does business in the standard way of producing price-competitive materials at large, integrated complexes. On the other hand, it funds medical services and the education of young people in the communities where it operates and also lends money to farmers that supply it with sugarcane.

“We have a strong sense of social mission that started with my grandfather, who was born poor,” says Samir Somaiya, Godavari’s third-generation chairman and managing director. “We take a very long-term perspective to business.”

The company was founded in 1939, when the elder Somaiya, after enjoying some success as a sugar trader, decided to start up his own sugar mill. In the decades that followed, Godavari’s business thrived, partly because it was protected by Indian import tariffs. When his grandson Samir Somaiya joined the company, those tariffs were in the process of being dismantled. The company had to close plants, a trauma that has guided Somaiya’s decision-making ever since.

“I decided to never rely again on tariff protection,” Samir Somaiya says. He went further than that, reorganizing the business so success doesn’t depend on any specific set of conditions. “We don’t want to be vulnerable to any technology, any one process, any customer,” Somaiya says.

India is a major sugar exporter, and Godavari is one of India’s major sugar refiners. Under Somaiya, a basic tenet has been to extract more value out of sugarcane farming. Starting with sugarcane, Godavari refines sugar, ferments ethanol, and derives an ever-expanding range of biochemicals. From plantation waste, it extracts energy at cogeneration plants that are integrated with its mills and chemical plants.

Ethanol is Godavari’s starting point for a family of downstream chemicals. It converts ethanol into acetaldehyde and then acetic acid. From there it produces derivatives such as ethyl acetate, crotonaldehyde, 1,3-butanediol, and flavor and fragrance ingredients. The company calls itself one of the world’s top 10 producers of ethyl acetate, and it exports more than two-thirds of the chemicals it makes. With the launch of new biochemicals and the commissioning of more power generation capacity this year, the company expects its sales to surge by 25% to $250 million.

IT’S UNUSUAL for a major biobased chemical maker to emerge from the sugar business, according to Sarah Hickingbottom, business development manager for oleo- and biochemicals at LMC International, a consulting firm based in Oxford, England. Most biochemical firms own a specific technology they use to produce chemicals from purchased feedstock. Or they are chemical companies that modify a petrochemical process to use a biobased feedstock instead.

But as the biobased chemical business matures, access to competitive feedstock may win the day, Hickingbottom predicts. Production processes in this relatively new business will eventually become standardized. When that happens, having access to cheap raw materials will be key.

As a major sugar exporter, India is advantaged, Hickingbottom says. But the country’s output varies from year to year, she notes. In poor harvest years, companies that maintain close relations with local sugarcane growers will likely be in a better position to secure raw materials. In that context, it’s possible that Godavari’s philanthropic bent may help the company businesswise, even if that wasn’t the point. Paul S. Zorner, an American member of Godavari’s board who has worked at and advised dozens of biobased fuel and chemical companies, notes that the firm helps fund the studies of thousands of young people in the communities where it operates. Godavari also loans money, when the need arises, to the 20,000 or so farming families that supply it with sugarcane.

According to Somaiya, several family foundations that he chairs pay for the education of 35,000 students in communities where Godavari operates. They also fund a 500-bed hospital and a rural health center.

Zorner first met Somaiya at a conference on sugar in South Africa. He has now been on Godavari’s board for seven years because the two men share similar ideas about how to extract value from sugar. The company’s manufacturing operations are highly efficient, Zorner claims. “Godavari’s plants have a very good scale and are well engineered both chemically and mechanically,” he says. “The only thing that is wasted is CO2, really.” Godavari was able to achieve this efficiency thanks to India’s abundance of engineering talent, he adds.

IN FACT, the company’s biobased chemicals are produced so efficiently that they compete pricewise against identical products obtained from petrochemical sources. There was a time when companies expected to receive a premium for renewably sourced chemicals, but according to Zorner, it’s a rare case when that happens.

Even without a price premium, at least one investor sees opportunity in Godavari’s focus on products from renewable sources. The Mauritius-based private equity fund Mandala Capital last month agreed to inject $15 million in Godavari. The cash will help to support product development and pay for a new specialty chemical plant. Mandala didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article, but in an earlier statement, the firm said it endorsed Godavari’s strategy of getting more value from sugar.

The academic world also sees value in Godavari’s approach. Somaiya teaches a one-month chemical engineering course on biorefining every two years at Cornell University. More broadly, Zorner says, Godavari can serve as an inspiration to the many parts of the world that have strong agricultural sectors but little industry. “It just shows what you can accomplish with the sun, water, and some manpower.”

Click here to download the pdf file.

Daughters of Wireman and Farmer Score Over 90% at SSC Exam

TNN | Jun 16, 2015MUMBAI: Diligent daughters of a wireman and a farmer topped their schools in rural Ahmednagar at the recently concluded SSC exams in Maharashtra. Pooja Tribhuvan achieved 94% and Tanuja Kale scored 92.2%. Both are school toppers already.

Their schools Somaiya Vidya Mandir Laxmiwadi, and Somaiya Vidya Mandir, Sakarwadi, achieved 90% pass results. They were proud to have female students as toppers.

The children's achievement is remarkable for more than half of them come from underprivileged homes. Several are first generation learners whose parents work as farmers or labourers. Parents play an inclusive role in their education.

Pooja's father is a wireman and her mother works in a sweetmeat shop. She said, "I studied for two or three hours a day. I had a few difficulties studying Sanskrit and English but the school helped me overcome them.'' Her father Kailashrao said, "I had to give up my education and work to support my family. So I wanted my children to have the opportunity to learn. Pooja worked very hard. It was her 'jidd' (determination) that she managed to achieve what her father could not. My son has studied here too."

Sakarwadi principal Sunita Pare said, "Our topper Tanuja Kale, who is the daughter of a farmer, had also topped the National Talent Search last year. She is a very intelligent student and has worked hard despite financial difficulties."

Sakarwadi saw a pass percentage of 97.70 of which 20% passed with distinction marks. Besides Tanuja, Devyani Gagare scored 92% and Pratiksha More 91.6%. The Laxmiwadi school had a pass percentage of 91.3% with 16% students scoring distinction marks. Close on Puja's heels came Vrushali Ghane with 92.8% and Priyanka Paghire and Rudra Jambhulkar both with 91.8%.

The schools are run by Godavari Biorefineries in association with Somaiya Vidyavihar, Mumbai. Both institutes also provide visiting teachers and guest lecturers from Somaiya Vidyavihar, Mumbai, as well as experts from international colleges on occasion.

Samir Somaiya, president, Somaiya Vidyavihar, said, "It is the dedication of the school principals and teachers that creates the foundation for all great institutions. The children of the villages are dear to us and we are very proud of their achievements."

Click here to download the pdf file.

How Somaiya Vidyavihar Turned Two Rural Marathi Schools into Model Institutions

SOCIAL.YOURSTORY.COM | Jul 01, 2015Knowledge only liberates

“What you get from society, you must return multifold.” That, in short, was Padmashree Karamshi Jethabai Somaiya’s philosophy, which is entrenched in the values and work of Somaiya Vidyavihar, a trust he established in 1959. Born in the early 1900s to a poor family, he could not study beyond grade VI. In 1939, a poorly educated Somaiya built sugar factories in Sakarwadi and Laxmiwadi in Maharashtra. The sweet success of his factories gave rise to the K. J. Somaiya College of Arts and Sciences in Mumbai and the Somaiya Vidyamandir Schools in Sakarwadi and Laxmiwadi, where most of his employees lived with their families. The Sakarwadi school was built on the banks of the Godavari for children of the Kopargaon taluka, Ahmednagar. Today, poor children from neighbouring villages like Wari, Sade, Bhojade and Dhotre in Kopargaon,n and Nighoj, Shirdi, Rui and Dorhale near Rahata taluka travel to attend classes.

In the rural landscape of Maharashtra, the Vidyamandir schools underwent a transformation 13 years ago when the President of Somaiya Vidyavihar and Chairman of the Godavari Biorefineries Ltd, Samir Somaiya, visited them with his two-year-old daughter. The fateful visit resulted in the establishment of schools that boast of science laboratries, movie halls, libraries, computer laboratries and a music hall today. The village children of Kopargaon and Rahata were no different to him than his daughter. Feeling they deserved the same quality of education as English-medium schools impart, he was renewed with strong determination to turn Jethabai Somaiya’s sweat and blood into model Marathi institutions.

Samir’s belief in developing regional language schools into bastions of knowledge has brought to rural Maharashtra a robotics workshop by K. J. Somaiya College of Engineering and Information Technology; sociology students and professors from S. K. Somaiya Degree College of Arts, Science and Commerce to develop both schools; Cornell University faculty and students to discuss teaching methods and science experiments; and ex-directors of the Nehru Planetarium who conduct star viewing field trips and play space documentaries for students (the schools have their own telescope). Samir Somaiya feels being born in a taluka is no reason why rural children shouldn’t be exposed to the rich world outside. That commitment to quality education has led to near perfect results at both schools, which perform well not despite being Marathi institutions, but because of it.

Good schools make good teachers

A testament to how access to hygiene can make or break a child’s future in India, Pare says parents are more confident sending children to school when they know it has good toilet facilities, especially if the child is a girl. As Mid-Day Meals are handled by Godavari Refineries, there’s better quality control compared to government schools.

A testament to how access to hygiene can make or break a child’s future in India, Pare says parents are more confident sending children to school when they know it has good toilet facilities, especially if the child is a girl. As Mid-Day Meals are handled by Godavari Refineries, there’s better quality control compared to government schools.

Pare talks about how infrastructure is important to education, whether it’s spacious rooms or ventilation. The walls are decorated with charts and designs by students to give them an ownership of the space. Sports, from football and hockey to rural games, music and dance play an important role in the school. “All the students,” Pare says, “are encouraged to participate and perform well in the inter-school competitions at the taluka-, district- as well as state-level. To give the children greater exposure, we often hold district level championships. This allows our students to meet students from across the state.”

The girls of Somaiya Vidyavihar

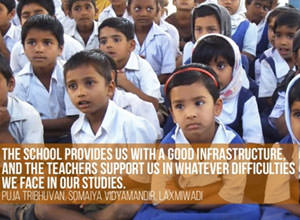

Puja Tribhuvan recently passed her SSC from Somaiya Vidyamandir, Laxmiwadi. From a very poor family, her father works as a wireman and her mother, in a sweet shop. She says, “We live in a rented house.” At Somaiya, Puja says she was only able to improve because of the unfaltering and patient support of her teachers. She especially found Sanskrit and English difficult before her teachers encouraged her. Puja says, “The school provides us with a good infrastructure, and the teachers support us in whatever difficulties we face in our studies.” She likes the visits by international guests and the routine Somaiya Vidyvihar visits from Mumbai.

Puja hopes to become an engineer one day. Ever since her impressive results, she has a renewed confidence, and genuinely believes that her aspirations are not fantasy. She says, “I can now look at the future with great hope and determination.” She adds: “Like our school teachers, other school teachers should be open and involved in the child’s development. They should be available to clear their doubts and difficulties so that students do not hesitate before approaching them.”

Devyani Gagare, from the same school, also has big ambitions. When she was only a child of four, her father abandoned the family. Ever since, she’s lived with her mother, a primary school government teacher. Girls in rural schools have very little exposure to sports, let alone a decent education. But with the backing of her teachers, Devyani is a state-level badmintonplayer, besides already being a district champion in table tennis. Devyani says, “The teachers are highly qualified,” and that the best part about her school is the sports facilities. Lucky enough to be a part of Somaiya Vidyamandir schook, she feels equally confident of her future as her peers.

In Sakarwadi, Tanuja Kale has just passed her SSC. Born to a farmer and housewife, she says she started school facing difficulties in many subjects. But with sustained effort on the school’s part, she was able to top the National Talent Search Examination.

Nevertheless, teachers like Pare have their work cut out for them. “For students with low-income backgrounds, even the basic needs are a challenge to be fulfilled. They do understand the importance of education, but are often not able to give the attention that it needs. For them, just making their daily living takes their time. They are not able to support their child at home for studying.” It’s easy to talk about preserving childhood, but poor students often have no choice but to lend a helping hand to support their families. When putting a meal in on the table becomes a matter of good fortune,, having an extra pair of hands to help is a desperate measure. “So,” Pare says, “we have to be understanding of their conditions, and ensure that the children remain motivated. Thus making education affordable and accessible is very important. Also important is for parents to see that the school is of a good quality, so making the sacrifices needed for the child to study there will be worth the effort.”

Link: http://social.yourstory.com/2015/07/somaiya-vidyavihar/

Click here to download the pdf file.

Making a Mark Despite the Odds

EI Staff | Jun 04, 2015

12 underprivileged students sponsored by ‘Help A Child’ achieve over 90% in the Karnataka State exams

Karnataka: In the recent 12th grade results in Karnataka, 12 students sponsored by Help A Child, an initiative of Godavari Biorefineries Limited, scored more than 90% in the exam and 3 students have scored 100/100 marks in Physics and Math. ‘Help A Child’ in association with Somaiya Vidyavihar provides scholarships to highly motivated students. The resounding success of this program has shown that children when given an opportunity have ability and a will to succeed despite insurmountable odds.

Abhishek Karadi, from S.R. Pre University College, Banahatti who has secured 95.66 % in HSC Commerce stream, said that “I come from a humble family background, where my father is a weaver and mother is a housewife. Even though I excelled in school and got 91.84% in the Xth exams, I never thought that I could study further for graduation, as financially it was not possible. Graduation was a distant dream. ’Help A Child’ sponsored my education. They not only

provided me with financial support but also moral support. This has helped me secure good marks in the 12th grade.”

Another topper, Dixita Vare who has secured 94.83% in HSC Science stream from S.R. Pre University College, had secured 94.24% in the Xth, Banahatti says, “I was planning to quit studies due to lack of finances, since I come from a very poor financial background, my father is a daily wage labourer and mother is a housewife. ‘Help A Child’ provided me access to textbooks, financial help and kept me motivated which made it possible for me not only study but also excel in my exams.

Further, one student Prashant Hangandi B.A III (S.T.C. College, Banahatti) has bagged two gold medals in Economics and Geography subjects from the Rani Chennamma University, Belgaum. He did B.A from S.T.C. College, Banahatti and scored 89.93% in final year.He has been sponsored by ‘Help A Child’, since 2009.

Samir Somaiya, Chairman, Godavari Biorefineries Limited says, “Education is the backbone of every society in this world. However, underprivileged children from rural areas often have to drop out from school denying themselves access to quality education and professional skills and continuing the cycle of poverty.We aim to reach out to those who need our help the most, to ensure that they do not have to give up their education simply because of a lack of funds.”

He adds, “Much more needs to be done. Many individual and corporates have joined hands with us in this initiative, sponsoring students for their higher education. Many of our ex-students today have become sponsors. We are proud of the achievements of our students.”

Nandan Mehta, who has sponsored a student through Help A Child says “ I have supported Help a Child for some years where I have had the opportunity to witness growth and development of the child I supported. The importance of enabling Higher Education, especially of rural and underprivileged children, can be really understood when one meets these children and sees their determination to achieve in life. I am very happy to be able to contribute towards this initiative”.

Students who achieved over 90% are Abhishekh Karadi, Dixita Vare, Shrinath Raval, Vinod Baogi, Sahana Savadi, Aditya Madar, Pooja Geddappannavar, Rohini Dhingane, Manjunath Madarkhandi, Preeti Sultanpur, Mahalaxmi Hangandi, Anusha Muragundi.

Link: http://www.educationinsider.net/detail_news.php?id=2194

Click here to download the pdf file.

A Bitter Harvest

Business India | Sep 14, 2015Correct the mismatch in pricing and save the sugar industry

It is a super industry, and we need to look at it from an advantageous point of view:

It is a super industry, and we need to look at it from an advantageous point of view:

- Millions of farmers grow cane in large areas of the country

- Cane is among the most remunerative crops for them (if policy is good), and also hardy (it can with stand drought and flood better than many).

- India is the largest consumer of sugar in the world.

- From cane, a variety of by-products such as ethanol and power can be produced.

The problem that the sugar industry faces is one of oversupply of cane. This is primarily due to high announced prices (fair and remunerative price or FRP) and returns. Any farmer faced with a good price pronouncement of cane will plant more. This then leads to an oversupply of sugar, which will automatically depress the price of sugar. Prices need to be based on economics, and only then will this mismatch be corrected. Thus, sugar prices are low, and cane prices are high, making the payment of cane price, the FRP impossible. And this will not change, unless this mismatch is corrected.

In recommending the FRP, the CACP (Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices) had suggested the cane price, with the proviso, that if the frp was higher than the economically linked Rangarajan formula (this price links the price of cane to the price of sugar, molasses and bagasse), then the difference should be met by the government, through some stabilisation fund. The government announced the FRP by only looking at FRP number, and overlooked the suggestion of the price difference. So, one option is for the government to pay this difference.

The other approach is to create demand. This can be done by:

The other approach is to create demand. This can be done by:

- Buying sugar for a ‘strategic reserve’. This can work once or twice, but a long-term natural demand must be created.

- The government should give a subsidy for exporting sugar (raw, white or refined). A subsidy for raw sugar was announced, but at the end of the season, so by the time the price was announced, the season was almost over, and the raw price had fallen.

- Creating a programme that encourages the use of sugarcane for production of ethanol, biochemicals, sugarcane for production of ethanol, biochemicals, or even electricity, so that mills have alternate revenue streams, as well as options to put their surplus sugar. The government has just announced an excise exemption for ethanol used in fuel, this is good. Policies can be examined for examining the same for bio-refineries, and also giving good prices for power through the implementation of recs (many states such as Karnataka, are not following the recommendations of CERC for RECs).

Further, since sugarcane pricing will always be politically sensitive sugar prices will always have to be protected by high import duty. Not because the industry needs protection, but because the cane price, and therefore the farmer, needs protection. The recent policy measures raising import duty, etc, are good in the long run, as an insurance against Brazilian or international low prices.

It is best to follow the Rangarajan formula – linking the price of sugarcane to sugar, molasses and bagasse – the primary by-products. This is done in Brazil, Thailand, and almost everywhere else.

The high prices of cane, those too high to pay, result in some farmers getting a very high price, and some get nothing. This leads to poverty and a crisis. This is industry provides employment to lakhs of people and even many more million farmers.

The author is chairman and managing director, Godavari Biorefineries Limited.

Click here to download the pdf file.

PE Firm Mandala Capital Invests Rs 96 Crore in Godavari Biorefineries

Economic Times | May 12, 2015

MUMBAI: Mandala Capital, a private equity firm focused on agribusinesses, has invested Rs 96 crore, or $15 million, in Godavari Biorefineries, a Mumbai-based company that manufactures foods, biofuels, specialty chemicals and other products using sugarcane as the primary feedstock.

The company will use the money to set up a new manufacturing plant for specialty chemicals and increase ethanol production capacity, besides for research and development.

Founded in 1939, Godavari has a capacity to manufacture more than 70 million litres of ethanol, which it uses to make chemicals for making paints, printing inks, pharmaceuticals, flexible packaging, fragrances and cosmetics. Godavari counts Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages and BASF among clients. "Our focus is on developing new production processes to manufacture specialty and high performance chemicals using biomass as raw materials within the value chain," said Godavari Biorefineries chairman Samir Somaiya.

Click here to download the pdf file.